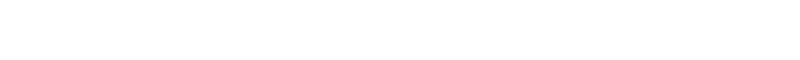

In a press conference on the day after the tragedy, Chancellor Harry Ransom expressed his gratitude for those who displayed heroism saving victims while he powerlessly watched from his office in the tower. Would being an eyewitness of the shooting affect the decisions he made on behalf of the university? This question is hard to answer. Much of the administrative response concerning the shooting was handled by Vice Chancellor Norman Hackerman of the Division of Academic Affairs. Hackerman notified professors of injured students asking them to provide special consideration due to the tragic circumstances. It is unclear what “special considerations” Hackerman meant, whether this related to classes missed due to time in the hospital or their emotional and mental well being.

Video clip courtesy of the Texas Archive of the Moving Image

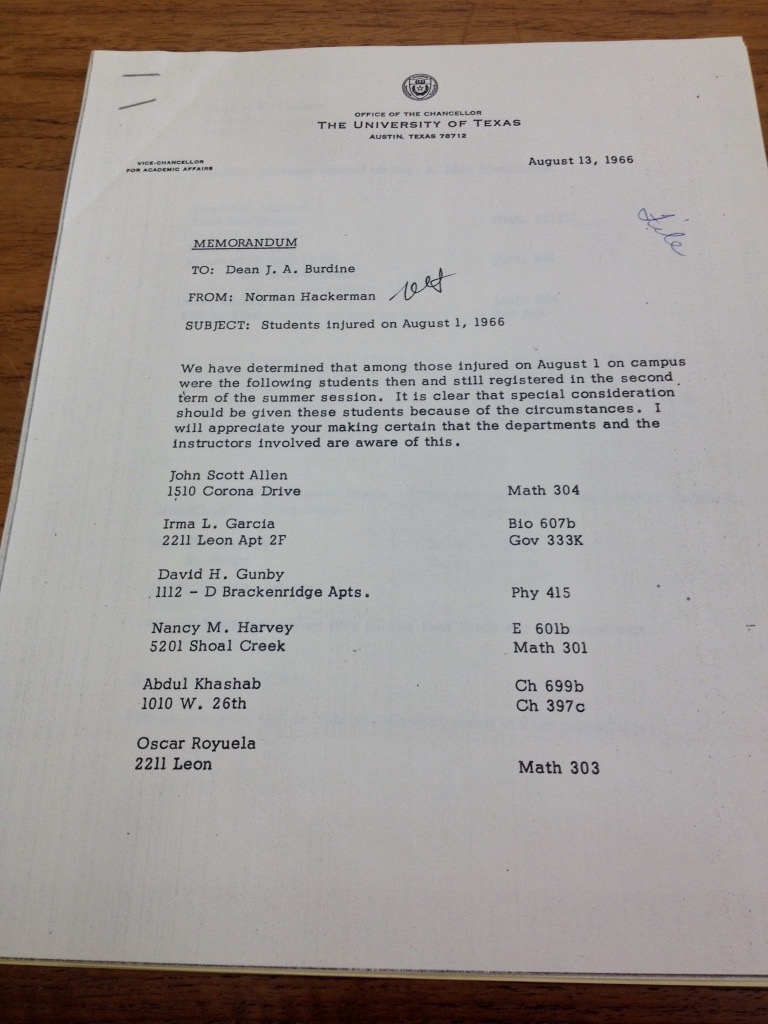

Money was raised by the UT Alumni Association and the Student Association to aid in the recovery of injured students in response to a suggestion from Chancellor Ransom. The university sent telegrams to injured students as well, concerned about their well being, although no effort was made to send out additional telegrams or letters to these same students. An inquiry was sent to Hackerman after this first batch of telegrams was sent asking “if you think it would be a good idea to send a [follow-up letter],” but no record can be found if this was done.1 Classes were canceled on August 2, allowing students, faculty, and staff to grapple with the shocking events of the previous day. Flags were flown at half-mast in remembrance of UT victims the week after the shooting. Additionally, a separate memorial fund was created for Edna E. Townsley, the receptionist at the tower observation deck killed by Whitman and leaving two children behind. The tower observation deck was not closed in response to the shooting, but instead closed by the Texas Board of Regents in 1974 after a number of suicides.

Dr. Hackerman’s memorandum asking for faculty to provide “special consideration” towards student’s injured during the shooting.

These actions must have appeared sufficient at the time, but today seem to lack concern for those not physically injured by the shooting. Where was the concern for how everyone else on the campus would grapple with this event? Was the eventual neglect of the shooting the university’s attempt to return campus activities to their normal routine?

No official commemoration or acknowledgment of the deadly tragedy took place in the years that followed. Only after decades of neglect, some members of the public began to take remembering the shooting into their own hands. In 1996, Dr. Rosa Eberly, a rhetoric professor at UT, held an undergraduate class titled “The UT Tower and Public Memory.” Her students interpreted this class as a call to action; to gain access to the tower’s observation deck. These students wrote a letter to then president Robert Berdahl protesting the need to reopen the tower’s observation. They received a letter in response denying access on the basis of the official policy of the Texas Regents to keep the observation deck permanently closed At the 30th anniversary, in 1996, the University Baptist Church, close neighbor to the campus at 21st St and Guadalupe St., organized a commemorative event with University officials in attendance. Perhaps this reignited interest in remembering the shooting within the UT community. In 1999, a committee was formed by the university to create a memorial in remembrance of the UT Tower shooting. Why did the university wait this long to create a memorial for the shooting, 33 years after the events? At that time, it seemed to Larry Faulkner, the sitting president of the university, that “the university’s stance had always seemed to be to try to erase what had happened, but with absolutely no success. It was like an injury that would never heal.”2 President Faulkner was a graduate student in chemistry at UT in 1966, walking off of campus soon after Whitman began shooting.3

Memo to Hackerman inquiring as to send additional telegrams to injured students.

University officials in 1966 felt their expression of sympathy was enough. Moving on and resuming everyday university life was more important to them at that time. In the 1960s many people believed that traumatic events were best left to be dealt with in the private sphere, not openly as a community. Those deciding how the university would respond were products of a generation that acknowledged tragedy but did not deem it appropriate to discuss openly. Had Chancellor Ransom or Vice-Chancellor Hackerman realized how traumatic this event was to the victims and the community, perhaps the university’s actions might have been different. By 1999 though, it was striking to President Faulkner and others that the university had not acknowledged the victims in a more visible way. Today, trauma is often dealt with much more immediate action and commemoration, compared to an age when time passed before trauma was dealt with appropriately.

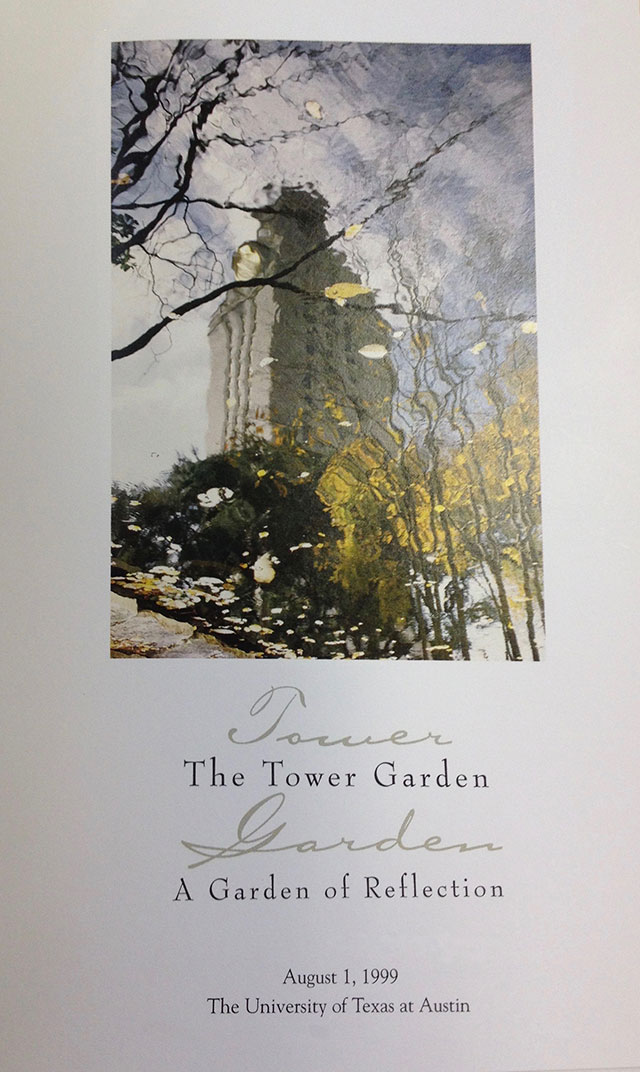

The handbill dispersed for the Tower Memorial Garden Dedication August 1, 1999.

The Tower Memorial Garden, the product of President Faulkner and the committee’s efforts to memorialize the event, is a garden located just north of the tower intended to allow visitors to remember, reflect, and process through their grief. Funding constraints prevented the memorial garden from fully illustrating the UT committee’s design as a space to not only remember the shooting, but process through one’s grief as a result of any situation. The garden was dedicated on August 1, 1999, 33 years after the shooting. The dedication was well attended, many expressing in comment cards written afterwards how thankful they were to have a designated spot on the UT campus to remember those whose lives were lost that hot August day. At the time, though, the garden did not include any kind of signage memorializing the victims of the shooting. In addition to the garden, the tower observation deck was reopened later that month as a way to reclaim the tower as a “symbol of education” and gain control over the tragic events of the shooting that occurred there. A memorial plaque was added to the garden in 2007, but did not include names of victims. Presently, a group not connected to the university is attempting to create a new memorial to the shooting, fifty years after the tragedy. Clearly, many people still find this garden and anonymous plaque insufficient to deal with the trauma of August 1, 1966.

In 1966 the university exhibited concern for the well-being of students directly affected by the shooting, so when did the UT and Austin community begin feeling that the university had not done enough? What is the appropriate role for a university administration to play when a tragic event happens on campus? What role does the administration play in shaping the ways the university community will continue to remember a traumatic event? Now that we understand more about the process of grief, perhaps we can provide counseling and services that aid communities to better process a tragic event on “safe place” like a university campus? These are questions people will continue to ask ourselves each year as any kind of tragedy occurs on a college campus.