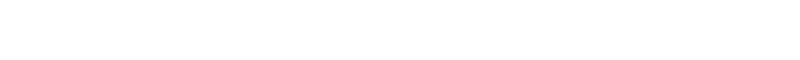

When the University of Texas tower was built in the 1930s it dominated the surrounding landscape. Only the Texas State Capitol, which sits nearly a mile south of the tower, rivaled its stature. Architect Paul Philippe Cret said that the tower was “the image carried in our memory when we think of the [University].”1 Other than being a symbol of the University, jokingly an “ivory tower,” the UT tower holds multiple exultant and tragic meanings.

For many, perhaps most, the tower, adjacent to the Main Building, represents what its official webpage claims: “Opened in 1937, it has become an icon, bathed in orange lights to celebrate academic honors or athletic victories, and serving as the backdrop for convocations, rallies, concerts and demonstrations. To alumni, the tower is a tether to the past; to all, the 307-foot tower is the definitive landmark of the University.”2 To the perpetually curious, and in line with the tower’s original function as the University’s main library, the inscription from the Gospel of John on the Main Building’s south façade provides inspiration: “Ye shall know the truth and the truth shall make you free.” But these associations only represent half of the story.

Image used with permission of the UT Austin Licensing Office

On August 1, 1966, the tower took on a new meaning when Charles Whitman ascended the tower and shot at the innocent below, killing fourteen people: “Instead of seeing the tower,” A Sniper in the Tower author Gary Lavergne said, “he saw a fortress,” a bastion for his dark inclinations.3 Whitman visited UT psychiatrist Maurice Heatley before committing his contemptible acts. During the visit, Whitman said that he was “thinking about going up on the tower with a deer rifle and start shooting people.”4 In a press conference after the shooting Heatley responded, “My interpretation of the remark was that it was quite transient. It meant he was hostile enough to knock down anything in his way.”5 When asked during the press conference if the tower represented a “site of some desperate action” for many students, Heatley said, “I think of [the tower] as mystic […] Perhaps it’s the romance of the tower in their eyes. They refer to the tower in known and proven superficial manners.”6 Heatley thought the phrase “I feel like jumping off the ole tower” was usually expressed in “affectionate terms,” an unhelpful view to say the least.7

Nine people indeed have died as a result of falling or jumping off of the tower.8 To those jumping, including an English professor, students – one after finding out that he needed three more academic hours to graduate – and a runaway from the State Hospital who “wanted to die so I wouldn’t cause any more trouble,” the tower represented an escape from life’s woes.9

Staircase to the Tower Observation Deck, 1966. Image courtesy of Texas State Library and Archives Commission.

The University permanently closed the tower observation deck in 1975 after the shooting and subsequent suicides. Once available to the public, the best view in Austin and the site of so much suffering was hidden from the eyes of Texas. The tower remained closed for nearly twenty-five years.

For many, the death associated with the tower has permanently changed its meaning. William Helmer was on campus when Whitman began his sniping spree. Twenty years later the specter of the tower still haunted him: “But if I’m walking from the Main Building across that wide concrete mall, say, or along one of the inner-campus drives, I can’t quite shake an ever so slightly uneasy feeling that the tower, somehow, is watching me.”10

In 1998, University President Larry Faulkner recommended reopening the tower following student insistence. Redefining the meaning of the tower was at the core of his recommendation. During a meeting of the Board of Regents, “President Faulkner noted that the tower is the most important symbol of academic aspiration and achievement in Texas, and it is the strongest image uniting members of the University community. He pointed out that, should this symbol of achievement remain closed to the public, the University community is left with only the history of unfortunate experiences associated with the tower and few occasions to create positive experiences for new generations.”11 The meeting was adjourned with a gavel made of timber from the original Main Building to commemorate the reopening.

Image used with permission of the UT Austin Licensing Office

Others eagerly agreed about “reclaiming” the tower. Charles Locke, the former tour coordinator at the tower, said, “One of the benefits of reopening the tower is that we can reclaim it as a symbol of academic excellence represented by the university.”12 At the thirtieth anniversary memorial service of the shooting commemorating the victims, Pastor Larry Bethune noted how the memorial erected near the turtle pond just north of the tower “will assist UT in reclaiming the tower as a symbol of life and hope.”13

But, despite any amount of effort, tragedy still haunts the tower. The walls still talk – if you know where to listen. The south façade is scarred with refilled pockmarks formed by bullets shot from below. The northwest corner, where Whitman was killed, has a tiny piece of stone cut out where a bullet struck. The beautiful view contrasts inevitable macabre thoughts. The tower’s official webpage casts a cheerier atmosphere and does not mention Whitman, but Derro Evans’s harrowing 1967 words still suffice: “The tower has still to be purged, for the memory of terror remains too harsh and too real to pass into darkness.”14 Nobody defines the tower for everybody; its associations and meanings are distinctive to each individual. The tower is not a monolith.