I hadn’t fully comprehended that lots of people around me in Austin not only owned guns but had them close at hand and regarded themselves as free to use them.

When it comes to armed civilians, the UT tower shooting is a singular occurrence. To my knowledge, there are no other recent examples of a group of armed civilians, without any prior communication or planning, teaming up to fire back at a gunman in a public venue, even as the police and other officials were responding to the shooting.

In the press reports after the shooting, nobody seemed particularly fazed by the large number of armed civilians present on the UT Campus that day. To the contrary, with very few exceptions, they were treated as heroes. The few people who thought that this sequence of events was anything out of the ordinary were outsiders like J.M. Coetzee. The South African-born author was attending the UT Austin on a Fulbright Award, and thus hadn’t grown up with the Texas gun culture.

At this point, the link between Texas and guns is treated as an immutable law of nature. The venerable magazine Texas Monthly has published at least two special issues (April 2016 and May 1995) devoted entirely to exploring the relationship between Texans and guns, and articles like this one and this one that show a widespread perception of Texas as “gun friendly” are common. The day after the UT tower shooting, stories published in the United Kingdom explicitly blamed the number of guns in American society for what happened, and said that “sudden violence was familiar in America.”1 Though a gross oversimplification of what happened, they were right in one regard: Texas is inextricably bound up in the story of the US gun culture. In order to more fully understand what happened on the UT campus that day, we have to take a step back and examine how guns came to occupy a central place in Texas culture.

According to a 2007 report by the Switzerland-based Small Arms Survey, the US has a greater number of firearms per capita than any other nation, and between 35 and 50 percent of civilian-owned guns are owned by Americans.2 In 1966, the percentage of US households with guns was around 50%, with those in the South 22% more likely to own guns.3 Those rates have fallen in the last few decades. Now, fewer than a third of Americans own guns.4 Despite this downward trend, the total number of guns owned has increased.5

The conventional explanation for why guns are so widespread in American culture is that ever since disembarking from the Mayflower, and especially since volunteer militias fought for independence from the British, Americans have loved guns. Thus began a tradition of gun ownership that has remained intact until the present day.6

Recently, this interpretation has been called into question. The historian Pamela Haag has argued that America’s current gun culture was the result of work done by early gun industrialists like Oliver Winchester and Samuel Colt. While guns have been present in America for centuries, they were primarily viewed as unexceptional objects. They were tools, necessary parts of frontier life or working on a farm. In order to expand the market for guns, though, they would have to be something more.

An advertisement for Winchester Rifles from 1895. In this ad and others from this period and earlier, guns were marketed as tools, text-heavy ads extolling their mechanical virtues. Image courtesy of Wikimedia

As it happens, the state of Texas was instrumental in Samuel Colt’s push for a wider market for his guns. William Hosley has written that Gen Sam Houston, Texas’ first senator to the United States in the 1850s, lobbied heavily for the adoption of Colt’s revolvers, saying that they should be used by every soldier on the frontier in order to prevent a “general Indian war.”7 Another key purchaser of Colt’s weapons was the Texas Rangers, whose members wrote about how the gun allowed them to take on groups many times their size.8 These early associations with Texas would be instrumental in Colt’s later advertising campaigns.

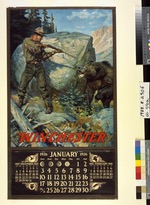

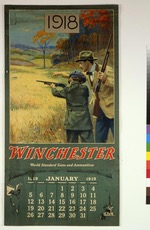

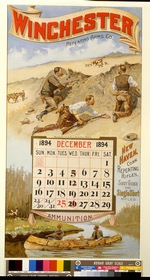

However, because the Civil War left the market flooded with weapons, many of the early gun industrialists nearly went out of business. Part of the problem was that guns were still viewed and marketed as tools, used by soldiers and frontiersmen.9 If they were to stay in business, they would have to change how guns were viewed, from tools to objects of love. The solution came in the early 1900s, when manufacturers switched from text-heavy ads touting their guns technical virtues to more emotive, visual ads that combined nostalgia, excitement, and romance in a potent mix.10 Many of these scenes would depict hunters or cowboys out West. They would also associate guns with masculinity. The text of one ad for Winchester from the 1910s said that one their rifles would “make a man of any boy,” thus marking guns as a rite of passage.11 Colt would use many of the stories and images of the early Texas Rangers in marketing his weapons, linking the two in the public mind and laying the groundwork for the gun culture we see today. Guns were no longer just tools that you would use like a shovel. They were a potent symbol and a marker of identity.

Three examples of some of the images used on Winchester calendars used to sell rifles. The images were richly colored and presented a far more emotive emotive image of guns that made them items of symbolic significance, not just tools. Images courtesy of the Buffalo Bill Center of the West

Popular media would also play a key role in fostering gun culture with the production of Westerns. Between 1950 and 1961, Hollywood produced over 600 films set between 1866 and 1890, the vast majority of them westerns. By 1959, there were 30 western TV shows running in primetime, and they made up 8 of the top 10 shows. And book publishers sold an average of 35 million paperback westerns a year.12

The final piece of the puzzle when considering Texas gun culture is hunting. After World War II, many soldiers returned home with a new interest in firearms. They joined the National Rifle Association, which was then mostly concerned with marksmanship. However, the returning soldiers were more interested in hunting, and consequently the NRA’s magazine, American Rifleman, switched its coverage to emphasize hunting at the expense of target shooting.13 This is borne out by polling data from the 1960s, which shows that over 80% of the weapons owned were shotguns or rifles, implying that they were primarily used for hunting.14 The survey didn’t examine numbers by state, but it’s safe to assume that Texas followed this trend closely, given the importance of firearms in rural life. In reflecting back on his collection of firearms, the writer John Graves emphasized how central guns were to everyday life, from keeping the land clear of varmints to fending off rattlesnakes. It also was a way of bonding with his father. The journalist Robert Draper noted something similar in his piece on a group of hunters in East Texas. Hunting wasn’t just for sport or sustenance. It was a bonding ritual.15

It’s important to keep this aspect of bonding in mind. Charles Whitman grew up in Florida, which also has a history of gun ownership, where his father taught him how to use firearms from an early age. It was one of the ways the two men related to each other, and it was one of the few things about his son that the elder Whitman praised unreservedly.16 From an early age, Whitman had hunting in his blood, as did many of those who shot back at him.

One particular article, titled “Arsenal Ordinary in Texas,” published by The Austin Statesman on August 4, 1966, is useful for illustrating the ubiquity and banality of guns in Texas. It examined the arsenal that Charles Whitman took with him to the top of the tower. When Austin police officials went through the footlocker Whitman dragged up there with him they found four rifles, two shotguns, and five pistols, along with a substantial stockpile of ammunition and other supplies. To those who did not grow up in a gun culture, this collection sounds excessive. However, several sportsmen said afterwards that arsenals this size and even larger were not uncommon in Texas households. The secretary of the Texas Senate himself reported owning six rifles, three shotguns, and a pistol.17

The Austin Police Department recorded the contents of Whitman's trunk that he brought with him to the top of the tower. His stockpile demonstrated that he was planning on holding out for a substantial period of time, but area sportsmen didn't regard his collection as anything out of the ordinary. Images courtesy of Austin History Center, Austin Public Library

The article also listed a few statistics on the number of weapons in Texas at the time. In the first seven months of 1966, the Department of Public Safety said that they had reported sales of 175,768 pistols. The previous year, the state had issued 571,058 regular resident hunting licenses, with an estimated 160,000 license exemptions issued to people under 17, over 65, or who wished to hunt on their own land. The total population in Texas at the time was about 10.38 million.

There is one further thing that this article tells us. It states that at the time, private citizens were not allowed to carry pistols. However, Texas law was mute on the subject of rifles and Texas sportsmen were among the most vocal opponents of any sort of gun control legislation. Immediately after the shooting, there was general outcry for greater gun control, but it was staunchly opposed by Earle Cabell, a representative from Dallas, and many others, on the grounds that new gun laws wouldn’t have stopped Whitman and would unduly punish sportsmen.18 In the end, the legislation would stall until after the assassinations of Robert F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968.

To be clear, many people still viewed the rifle as a tool, a necessary part of life on the ranch or the farm. But in many ways, it was like a shootout in an old western, with people playing the roles modeled for them by cowboys and Texas Rangers. Could this have happened anywhere else? Some academics have hypothesized on the increased level of violence in southern society, especially in vigilante or “defensive” situations.19 There’s little empirical evidence to back this up, so the question is left open. Was there something peculiarly American, or southern, or Texan about dozens of armed civilians appearing on a public university campus? Is this sort of violence inevitable in a society that attaches mythical status to guns, produces media saturated with gun violence, and sees firearms as part of its history from its earliest days? I won’t pretend to know the answer. All I can do is echo Allen Crum’s statement, which he gave to American Rifleman in 1966: “The right of the private citizen to bear arms was never more graphically demonstrated than on the University of Texas Campus Aug. 1, 1966.”