When Charles Whitman went to the top of the UT tower on August 1, 1966, the university did not have a commissioned police force and the Austin Police Department was unprepared to respond. Both of these things made it possible for Whitman to continue his killing spree for 96 terrifying minutes.

When the shooting was over and the bodies were removed, the media, public officials, and citizens alike called for answers and wanted action. Everyone was trying to make sense of the tragic event and try to prevent it from happening again.

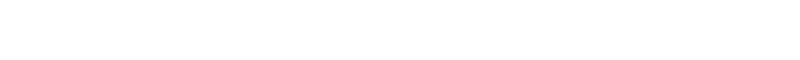

Letter from APD Chief Robert Miles to FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover. Austin (TX) Police Department Records of the Charles Whitman Mass Murder Case. AR 2000.002. Image courtesy of the Austin History Center

There was widespread acknowledgement that the current security services of the campus were inadequate to deal with situations such as the Charles Whitman shootings.

For many the UT Traffic & Security Services (T&SS) were considered the de facto police department for The University of Texas. Their main focus was writing tickets for parking violations, supervising traffic, providing security around campus (including night watch of campus buildings), and conducting investigations. Investigations typically ran the gamut from vandalism and theft to drinking and campus hijinks.

Led by Chief Allen Hamilton, the department effectively managed its role and carried out its assigned duties. The T&SS, however, did not have commissioned police officers and did not carry weapons. It would be a significant shortcoming in their response to the shooting.

The official T&SS Offense Report from August 1, 1966 shows a department that responded quickly to the shooting by reaching out to Austin PD and the Department of Public Safety to try to coordinate action and establish lines of communication. They also acted to ensure student safety on campus by deploying officers toward the tower with speakers to warn students about the situation. Hamilton further communicated with the Women’s Dormitory to have all female students remain inside until the situation was resolved. Sgt. Barr was dispatched to help lead APD officers through university underground tunnels so they could gain access to the tower.

UT Traffic & Security Services Offense Report, officer statements, and other correspondence regarding security operations on the day of the shooting. UT Traffic and Security Services Chief Allen R. Hamilton Tower Sniper Records. Images courtesy of Dolph Briscoe Center for American History

At 11:50 am security officers L.W. Hebert and Jack Rodman were dispatched to the tower to check out the situation. Upon reaching the 27th floor by elevator they came across several of the early victims in the stairwell up to the 28th floor. After hearing continued gunfire outside and recognizing they had no weapons or plans by which to engage the shooter, both men decided it was best to head to the bottom of the main building to lock it down so no one could get in or out and to secure the interior of the building. This was at approximately 11:55 am. It was not until 89 minutes later that Whitman was finally shot and the killing ended.

The lack of adequate resources, firearms, and response plans greatly limited the university officers’ ability to act. This was grossly obvious when Chief Hamilton called the university ROTC program to see if they had any weapons that the Traffic & Security Services could use. The ROTC responded that they had weapons but no ammunition.

Letter from Texas Governor John Connally to APD Chief Robert Miles. Austin (TX) Police Department Records of the Charles Whitman Mass Murder Case. AR 2000.002. Image courtesy of the Austin History Center

The lack of weapons and organization was not solely a problem for officials of The University of Texas.

At the press conference held by the Austin Police Department immediately after the shooting, Chief of Police Robert Miles focused almost exclusively on the bravery of his officers and their attention to department policy. He likely did so for two reasons: first, to show that the department acted heroically, and second, to deflect questions about the overall preparedness and implementation of the department response. The bravery of the responding officers is without question. Their courage – not any standard plan of action – helped to eventually end Whitman’s rampage. The officers, however, did not have any specialized tactical training or the needed resources for clear communication. There was also no Incident Command System (ICS), or Unified Command, or any other framework for plan of action.

Notably, Chief Miles was at Brackenridge Hospital during the shooting - most likely in response to the shooting of Officer Billy Paul Speed. He was not, however, setting up a central command post or coordinating police action. Miles stated of the police response during the UT tower shooting, “In a situation like this, it all depended on independent action by officers.”1

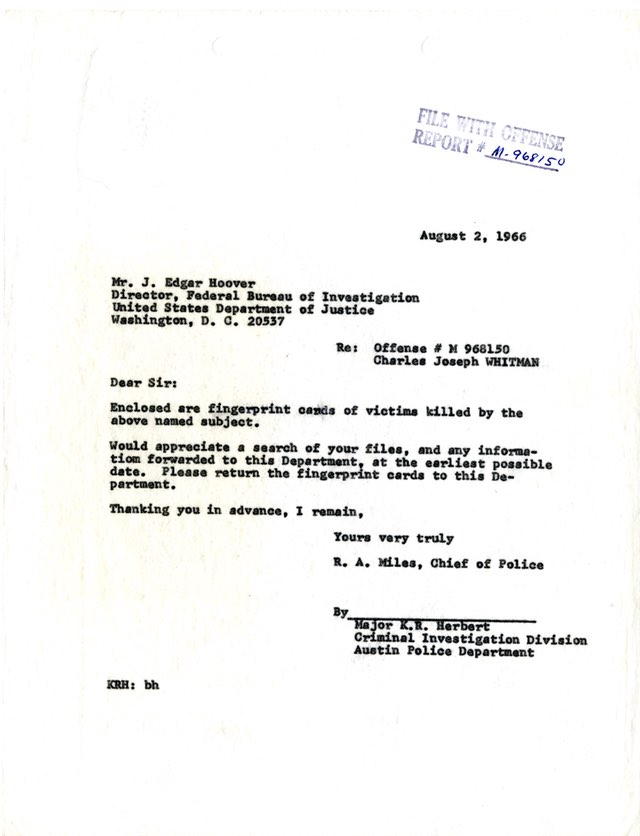

Wire report about the UT tower shooting. Ira Iscoe Papers. Image courtesy of Dolph Briscoe Center for American History

The UT tower shooting along with the Watts riots of the previous year produced a national consciousness about the need for new specialized training and resources for responding to violent events. Across the nation, police departments reviewed their preparedness, training, and capabilities to effectively respond to such situations. Most found major gaps and massive issues that had to be addressed. Special Weapons and Tactics (SWAT) teams were developed as a direct response to the UT tower shooting. Since their development in the late 1960s, SWAT teams are now found in almost every police department that serves a population of over 50,000.

One of the reasons that UT security officers lacked weapons prior to the UT tower shooting was that institutions of higher learning such as UT did not have the right to train and commission police officers. That was, however, soon to change.

During the 1967 legislative session, Senator A.M. Aiken proposed Senate Bill 162, which was “an act providing for the protection, safety and welfare of students and employees … and for the policing of the buildings and grounds of the State institutions of higher education of this State.”2 The idea was to provide institutions of higher learning with police forces that would be able to adequately provide for the safety of their students.

Letter from woman in New York to Governor John Connally concerning the UT tower shooting. UT Traffic and Security Services Chief Allen R. Hamilton Tower Sniper Records. Images courtesy of Dolph Briscoe Center for American History

With overwhelming support from both houses, the bill moved through committee and legislative floors at exceptional speed. SB 162 was formally signed into law by Governor John Connally on April 27, 1967.

Senate Bill 162 laid the groundwork for the establishment of the University of Texas System Police Department and Police Academy. In the near 50 years since its first class graduated in 1968, The University of Texas System Police Academy has graduated over 2000 commissioned peace officers and currently oversees the protection of all 15 campuses within the system, as well as its more than 300,000 students, staff, and faculty.

With a nod to the realities of August 1, 1966, current UT PD officers undergo a variety of training programs such as Advanced Law Enforcement Rapid Response Training (ALERRT) as a means to combat threats on campus without having to wait for SWAT to arrive during an active shooter scenario.

The official responses to August 1, 1966 presented a collective acknowledgement that inadequate preparation as well as deficient resources hindered response times and coordination. Also present was a belief that laws written and action taken in response to the tragedy would ameliorate or eliminate such events from happening in the future. The last 50 years have seen increases in policing, tactical training, specializations, and improvements in resources and technology.

Have these improvements ensured crime prevention? Safety for all people? Fairness under the law? No.

It is however, the respect for human life that requires that even as there is no amount of preparation or weapons that can prevent all crime or has ensured the protection of all people, that safety and protection for each individual must be continually pursued.