When Charles Whitman shot at innocent passersby from atop the University of Texas tower on August 1, 1966, he shocked the country and, according to the local newspapers, became the “Greatest Mass Slayer in History.”1 Media across the country tried to explain what occurred to their stunned readers, and in Austin, three newspapers, The Daily Texan, UT Austin’s student newspaper, and the Austin American and The Austin Statesman, the citywide newspapers, shaped the public understanding of the events for shocked Austinites and UT students.2 Nationwide, newspapers reported extensively on the “sniper in Texas” and closely scrutinized the events of that day.3 All these articles attempted to answer the same question: “Why?” The Austin American-Statesman, published jointly on Sundays through 1973, chose to focus on Whitman’s mental and medical state, while The Daily Texan highlighted student voices and their efforts to assist those affected.

Student Voices Heard

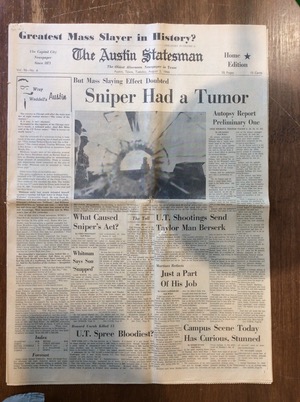

The Daily Texan, printed as The Summer Texan during UT’s summer session that year, acted as a voice of the student body. The student newspaper had a regular column, “The Firing Line,” for students to submit short comments to the paper reacting to current news. On August 9, 1966, “The Firing Line” was awash with opinions about the past week’s tragedy. Like the city newspapers, students’ commentary on “The Firing Line” raised many questions about the reasons Whitman chose to fire at innocent people from atop the tower.4 The students made various suggestions to improve safety, called for permanently or temporarily closing the tower, and recommended ways to commemorate those wounded and killed.

The tragic event affected people with ties to UT around the world. Pete Coneway expressed his condolences and said “that the world understands this terrible crime as the act of an insane person.”5 Nancy Kowert, John De La Garza, Jr., and David Gray each said the tower should remain open despite its tarnished image. Gray wrote “the Observation Deck of the tower should remain open – not for the curious nor the morbid, but so that people might see the bullet scars and blood stains and not forget that Whitman was indicative of something wrong in our society.”6 H. Gray Merriam’s submission, “Who’s Fault?,” [sic] echoed the same sentiments. Merriam did not view the “terror from the tower” as the act of one individual, and listed questions, wondering who to blame. The students generally did not feel the need to blame, but chose to move on, look to the future, and learn from a horrible event.

The “Theory of Disaster” and the Psychiatrists

The joint Austin American-Statesman released a special staff report on Sunday August 7, 1966 to try to explain Charles Whitman’s actions. The first page outlined community repercussions of the tragic event and several psychiatrists’ thoughts on Whitman.

Derro Evans and Sara Speights, staff writers at the Austin American-Statesman, viewed the shooting through a psychological and sociological lens, using Dr. Harry E. Moore’s “Theory of Disaster” to explain the responses of the UT community.7 Dr. Moore was a sociologist at UT who passed away a month before the shooting. His theory consisted of four stages: disbelief, aid, survivor’s feelings, and scapegoating. They saw “disbelief” in students’ initial reactions, who thought the gunshots were construction noises. Evans and Speights reported, as examples of “aid,” that many students ran out in the line of fire to help their fellow students. “Survivors’ feelings” were overwhelmingly uncertain: they did not know how to react. Many returned to campus the next day unsure of the next steps to take. As examples of scapegoating, they identified several targets of popular blaming: the psychiatrist who treated Whitman months before, police protocol, and the gun laws.8

Underneath this article was “The Psychiatrists: Right Before and After the Tragedy” by Chris Whitcraft, another staff writer. It detailed two different psychiatrist’s views of Whitman. Dr. Maurice Dean Heatly, the psychiatrist at UT’s Student Health Center, met with Whitman on March 29, 1966. Even though Whitman expressed his thoughts of “going up on the tower with a deer rifle and … shooting people,” Heatly determined Whitman had “no psychosis at all.” Dr. John A. Boston, a private practitioner and part-time assistant professor of Special Education at UT, labeled Whitman as a paranoid schizophrenic.

Whitcraft interviewed Dr. Clarence R. Miller, superintendent of the Austin State Hospital, to offer a third opinion. Miller said both men were right on the days they gave their diagnoses. Whitman was the “golden boy,” and would not have been committed on the day he gave Dr. Heatly the now, rattling statement, Dr. Miller said. He also added that Dr. Boston’s diagnosis is an easy one to make in hindsight.9

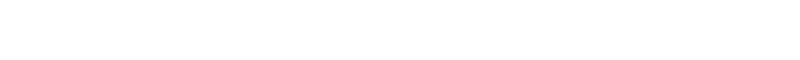

The Sniper had a Tumor

On the day after the shooting, The Austin Statesman presented another actor in the horrific incident. Plastered across the August 2, 1966 edition, the biggest headline on the page read: “Sniper Had a Tumor.”10 But, even though the headline suggested the tumor had an inherent effect on Whitman’s acts, the first sentence of the article states the opposite: “… an Austin pathologist conducting the post-mortem said he did not think it had a direct effect in sparking the massacre Monday.”11 Through the years since, the tumor has been the subject of controversy, with some articles claiming it did play a factor and others saying the tumor had no effect at all. Perhaps journalists thought that citing the tumor created a sort of justification for such a senseless murder.

Another word stands out amongst the countless headlines printed in the days after Whitman’s act: “Sniper.” As the media tried to figure out who could commit such a terrible act, writers began piecing together a portrait of the man on the tower. “Sniper” jumped out as the most commonly used word to describe Whitman and it dominated the headlines, both local and nationwide. LIFE magazine’s cover on August 12, 1966 stated “The Texas Sniper.”12 Was this term used to convey the accuracy with which Whitman shot that day? With the United States in the midst of the Vietnam War, was “sniper” a more recognizable term than “murderer,” a term that does not appear in any headlines?

Whitman’s portrayal in the media does not seem to shift over time. He is simultaneously called a “Good Man, Good Husband, Good Citizen” and “an Insane Killer.”13

What about the victims?

Those affected by the tragedy, the dead and wounded, are written about in simple terms and often placed in small spaces among the columns dedicated to Whitman. Maybe because this was deemed the first mass murder, perhaps the media was not sure how to write about the victims aside from issuing obituary-like articles. However, The Daily Texan continuously reported the collection of funds for victims and their families. On August 9, 1966, The Daily Texan reported that the Ex-Students Association was setting up a special committee to look into ways to help the families of the victims. Their next issue had an article about the fund and how to contribute. A year later, The Daily Texan reported that surviving victims received almost $2,000 in aid grants from the Association.

Unlike the city newspapers, which were more interested in explaining Whitman and his actions, the student journalists at UT wrote about the efforts made to help those within their community.

Why?

Over the years, the media has retraced the events of August 1, 1966 and continues to struggle with the same question: “Why?” The simplest question seems to be the hardest one to answer and the student and city newspapers have grasped at multiple solutions over the last fifty years. Newspapers served as the first line of information that shaped public opinion in 1966. Through their coverage of the events of August 1, 1966, The Austin Statesman, The Austin American, and The Daily Texan tried to define Whitman, his actions, and the events that unfolded the days after. The various questions that journalists raised, days and even years after the event, seem to have no concrete answer. However, it shows our inherent need to know the simplest, yet hardest, question: Why?