To burden others with your problems – are they problems? – is not right – however

To carry them is akin to carrying a fused bomb –

I wonder if the fuse can be doused –

If it is doused what will be gained

Will the gain be worth the effort put forth

But

Should one who considers himself strong, surrender to an enemy he considers so trivial and despicable

Charles Whitman wrote these lines sometime in early 1964. We know this only because he tells us so: at the top of the page, Whitman made a notation in the midnight hours of August 1, 1966, explaining the year as a time “when I was in a similar feeling as I have been lately.”1 That “fused bomb” was detonating as he wrote. Earlier that evening, Whitman had begun to unburden his “problems” onto the two women he supposedly held most dear and would continue to do so later that day, onto dozens of other innocent victims and their families, communities, and friends. That explosion reverberated throughout the country, which found itself at a loss over how a “hitherto sane individual,” and an “all-American boy,” no less, could commit such senseless acts of violence.2

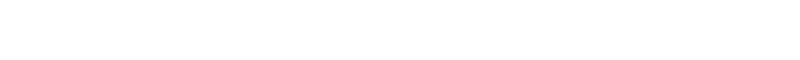

Whitman had a variety of unusual medical issues – an “unusually thin” skull, a “pecan-sized” brain tumor, and, as shown here, he was struck by lightning while stationed at Guantanamo Bay.

The debate over what made Charles Whitman “snap,” as it’s often put, began the day of his killings and will likely never end. Physicians, investigators, and researchers have spent years documenting his troubled home life, drug abuse, the infamous “pecan-sized” tumor discovered in his brain, and the personal demons he described with disturbingly clinical self-reflection. Certain additional, relevant details of his life have received surprisingly little attention. Some are simply bizarre, like the fact that he was once caught in a phone booth struck by lightning.3 Lightning strike survivors typically experience some level of long-term cognitive disabilities. More surprisingly, nobody bothered to get the perspective of his wife Kathy or her family about Whitman until just a couple of years ago, despite his admission to beating her on more than one occasion. Those perspectives have turned out to be quite damning. Meanwhile, speculation continues as to whether Whitman suffered from psychosis brought on by amphetamine-induced sleep deprivation and neuroscientists remain fascinated by the tumor and how much pressure it may or may not have exerted on his amygdala.4 Despite advances in neuroscience and psychology, satisfying answers to these questions continue to intrigue – and elude – us.

Immediately after the shooting, Texas Governor John Connally convened a thirty-two person expert committee to answer these very questions. Contrary to statements by individual practitioners, the committee’s report was decidedly inconclusive.5 Whitman’s body was embalmed before the autopsy, which made it impossible to conclusively check for drugs. His brain was damaged from the gunshot wounds that killed him. And the team lacked a recent psychiatric evaluation. The task force was forced to conclude that they found it “impossible to make a formal psychiatric diagnosis,” and “the application of existing knowledge of organic brain function does not enable us to explain the actions of Whitman on August first.”6

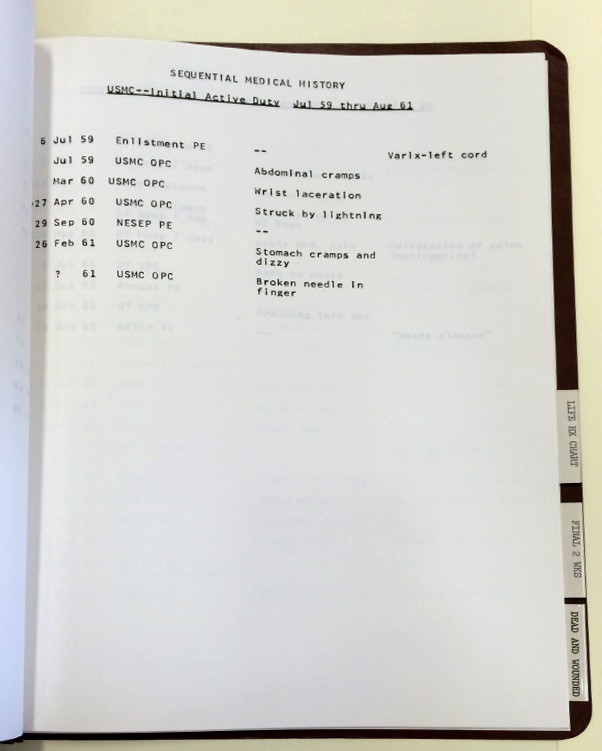

Archival wire print of Dr. Coleman de Chenar, who performed Whitman’s autopsy and concluded that the tumor pictured here was not the cause of the shootings.

The curiosity about Whitman and his motives has largely overshadowed an important part of the Governor’s Report. The committee’s recommendations on how to deal with the aftermath of the shootings, and try to prevent similar events in the future, went far beyond symbolic “thoughts and prayers.” The report helped to galvanize fundamental reform of mental health care practices at the University of Texas – a side of the tragedy’s legacy that has largely been forgotten.

Immediately after recommending the provision of aid to victims of the shooting, the committee’s next recommendation was “that The University of Texas have the best possible health program in the broadest meaning of the term for both students and faculty.” Mental health, in particular, was paramount. “For the university student, undergoing one of the most stressful periods of his development, a mental health program is considered vital – not only through implementation of known practices but also through ongoing research and application of new knowledge,” the report read. “No more fitting memorial to those who suffered from this tragic event, and no more worthwhile effort than to anticipate or prevent similar catastrophes, can be conceived.”

The scope and structure of UT student health services in 1966 was dramatically different than what it is today. Psychiatric and mental health services were provided by the “Mental Hygiene Clinic” of what was then called the Student Health Center. In addition, there was a Testing and Counseling Center that fell under the purview of the Dean of Students. While SHC’s mental health services were primarily clinical in nature, the mandate of the TCC in the mid-1960s was losing focus by the day. While originally intended to address academic issues, it had become increasingly clear that the stress and anxiety of university life – inside the classroom and out – called for a more holistic approach to student wellness.

Students at time were vocal about the quality and availability of counseling services on campus. Advice on both academic and personal issues, they said, was often cursory or unavailable. In March 1967, a committee of students from the university’s YMCA and YWCA called for reform due to a “student feeling that the University’s counseling system has been unable to respond adequately to some student needs and problems on this campus.”7 Since counseling was still regarded as a primarily academic issue, it was relegated in part to professors, who sometimes dismissed these duties as an undesired “extra job.”8 In a column for The Daily Texan two months after the shooting, Student Government President Clif Drummond called for the university to “re-define counseling and put students’ needs into a more realistic perspective.”

Now, I do not think it is the duty solely of the faculty to counsel. This aspect belongs also to professionals, student advisers, parents, and good friends. What is needed is simply to evaluate the roles and responsibilities of each of these counselors. Then their roles should be integrated into a broad program which has a coherent philosophical basis – not one which is fragmented.

Mental health professionals at the university were acutely aware that the school’s approach to mental health was fragmented. Dr. Ira Iscoe, a noted professor of psychology at UT, admitted that the TCC had developed in a “somewhat patchwork fashion.”9 This result was due to a combination of perpetually inadequate funding, a burgeoning student population, and changing attitudes towards the responsibilities of a university in the well being of its students. In fact, Iscoe and others had already begun a review of UT’s counseling policies several months before Whitman’s rampage. The UT Board of Regents had adopted a resolution in April 1966 to conduct the review, and Chancellor Harry Ransom convened the Ad-Hoc Committee on Student Counseling to carry out that task.

The committee was comprised largely of professionals from UT’s Hogg Foundation for Mental Health, which has been a pioneer in the field of mental health issues in Texas for the past 75 years. The Foundation played a key role in the restructuring and expansion of UT’s mental health services after the tower shooting. “Tragedy may serve as an immobilizer or a catalyst,” says its annual report for 1966. In this case, tragedy “accelerated programs already planned concerning campus mental health.” Indeed, the Foundation and its director, Robert Lee Sutherland, had been pushing for counseling reform on campus for years. In a letter to Ransom shortly after the shooting, Sutherland expressed frustration at past “research and pilot projects in counseling” that had been valuable but “fragmentary and inadequate,” and regret that a recent psychiatric consultation project was not continued past its trial year. “Its need,” Sutherland stressed, “is dramatically imperative in light of the Whitman case and other evidences of student problems.”10 We will never know whether the tower shooting could have been prevented by a reformed counseling system. What is certain, and what Sutherland was most concerned with, was that reform was needed to address “the educational progress and counseling needs of 28,600 students.”11

The Ad-Hoc Committee made its recommendations at the end of 1966. The TCC was split in two, and counseling services were expanded and re-defined. Additional annual budgetary funds were appropriated, approximately $250,000 for the SHC and its Mental Hygiene Clinic, and $103,000 for expanded student counseling services.12 Counselors were appointed to dormitories and a 24-hour hotline was established in the Dean of Student’s office.13 The hotline quickly demonstrated that the school had identified an unfulfilled need in the student community – students placed 1,088 calls to the hotline specifically requesting counseling during the 1967-68 academic year.14 In addition, the Hogg Foundation cited grants for “150 projects supervised in the last 12 months […] for pilot projects in counseling and related approaches” in its 1966 annual report. In one key development, it noted that “increased support by the administration and faculty” had been helpful for expanding mental health services. Support for these projects continued past the typical trial year, according to later annual reports. There was also a gradual shift in counseling philosophy. In an October 1967 follow-up, Dr. Iscoe noted that “the question of positive mental health is assuming more importance than the question of dealing with severely emotionally disturbed students.” This approach held that counseling should be available to all students on UT’s campus – not just those in dire straits. He clarified that the Mental Hygiene Clinic would be in charge of cases with “a clear psychiatric component,” but that the new Counseling Center should cooperate with the Clinic in appropriate situations (immediate and longer term considerations).15

Any discussion of the mental health consequences of the Whitman shootings must include the role of Dr. Maurice Dean Heatly. Perhaps the most scandalous revelation from the university in the days following the shootings was that Whitman had gone to the Student Health Center in March 1966 and told Dr. Heatly, a staff psychiatrist, that he was “thinking about going up on the tower with a deer rifle and start shooting people.”16 Heatly did graduate from medical school – he was in the class of 1939 at Baylor – but he was not board certified to practice psychiatry.17 At the time, no such certification was required to practice psychiatry in Texas. Any licensed physician was free to do so. Be that as it may, our knowledge of Heatly’s counseling style does not inspire confidence. Writing for Texas Monthly on their twentieth anniversary of the shooting, former student William Helmer recalled the sessions he and his wife had with Dr. Heatly:

My visit consisted mainly of listening to him talk on the telephone with the driller who was putting in a water well on his ranch, after which he gave me a prescription for Librium. My wife came back from her visit crying and said that after pretty much baring her soul, his advice to her was “Grow up.”

It is hard to say whether Helmer’s experience with Heatly was typical or not. What we do know is that the doctor was paid a total of $36,880 (about $265,000 by today’s standards) for his part-time work at the university between 1963 and 1967.18 We also know that Heatly’s career was marred by allegations of cronyism. His brother was the infamously iron-fisted State Senate Appropriations Committee Chairman William S. Heatly. In 1964, auditors found that Maurice Heatly had been paid $40 to $50 more per hour than other psychiatric consultants for his work for the Texas Department of Corrections and the Texas Youth Commission.19 The doctor denied any impropriety, and the whole affair was brushed off as an example of the TDC’s “woefully poor management techniques.”20

Allegations of misconduct in the Whitman case were similarly dismissed. Mental health practitioners at the time generally agreed that there was nothing he could have done to prevent the shootings later that year. “Thousands of people – and I mean literally thousands talk to doctors about having such feelings,” University of Chicago Psychiatrist Robert S. Daniels told Time – “Nearly all of them are just talking.”21 In a statement that reminds us of the political climate in 1966, New Jersey Psychiatrist Henry A. Davidson put a finer point on it: “We are in a situation now where there is enormous pressure for civil rights. The idea of locking someone up on the basis of a psychiatrist’s opinion that he might in the future be violent could be repugnant.”22 Governor Connally was even more forgiving, saying “I think Dr. Heatly was absolutely correct in the actions he took.”23 Mental health professionals at UT noted that there was no psychological test to identify potential killers and Dr. Iscoe characterized Whitman’s actions as an “enigma.” “It would be easier to understand,” said Iscoe, “if he had been one of the campus Beatniks, bearded, unkempt and on scholastic probation, aimlessly protesting a variety of things and meandering along with no purpose in life. Which would you keep your eye on as a potential trouble maker?”24 While it is difficult to judge Heatly’s responsibility in the Whitman case, suffice to say that he would probably not be hired by today’s Counseling and Mental Health Center – each of the center’s current M.D.s holds a board certification in psychiatry.

In heeding the call of the Governor’s Report, the University of Texas refused to be defined by tragedy. The shootings were a wake-up call to the school’s administration, which stepped up to support the Hogg Foundation in reforming and expanding access to mental health and counseling services on campus. General health services improved as well. By 1969, the alumni magazine, the Alcalde, was singing the praises of the newly augmented Student Health Center.25

Today, UT Austin is recognized as a leader among American universities for its approach to physical and mental wellness. The quality and scope of these programs continues to improve, as do efforts to expand access. That expanded access, however, has been met – and exceeded. Demand for mental health services on campus is currently well beyond capacity. In some cases, waiting periods for a counseling appointment in 2015 stretched to over a month. Other barriers to access have caused concern among the student community, in particular, a fee hike implemented this year for individual counseling and psychiatric sessions. With the implementation of “campus carry” beginning on August 1, 2016 – fifty years to the day since the shootings – this demand is likely to increase. Some faculty are concerned that the combination of mental stress and access to guns will put students at increased risk for suicide. While the university’s Working Group for Campus Carry policy called for the administration to “examine the level of resources devoted to mental health services and better publicize the existence of mental health services already available to the UT community,” the president’s policy recommendations did not mention plans to do so.

As we approach this fateful anniversary, it is worth pausing to reflect on how dramatically the mental health environment on campus has changed. And why it has changed.