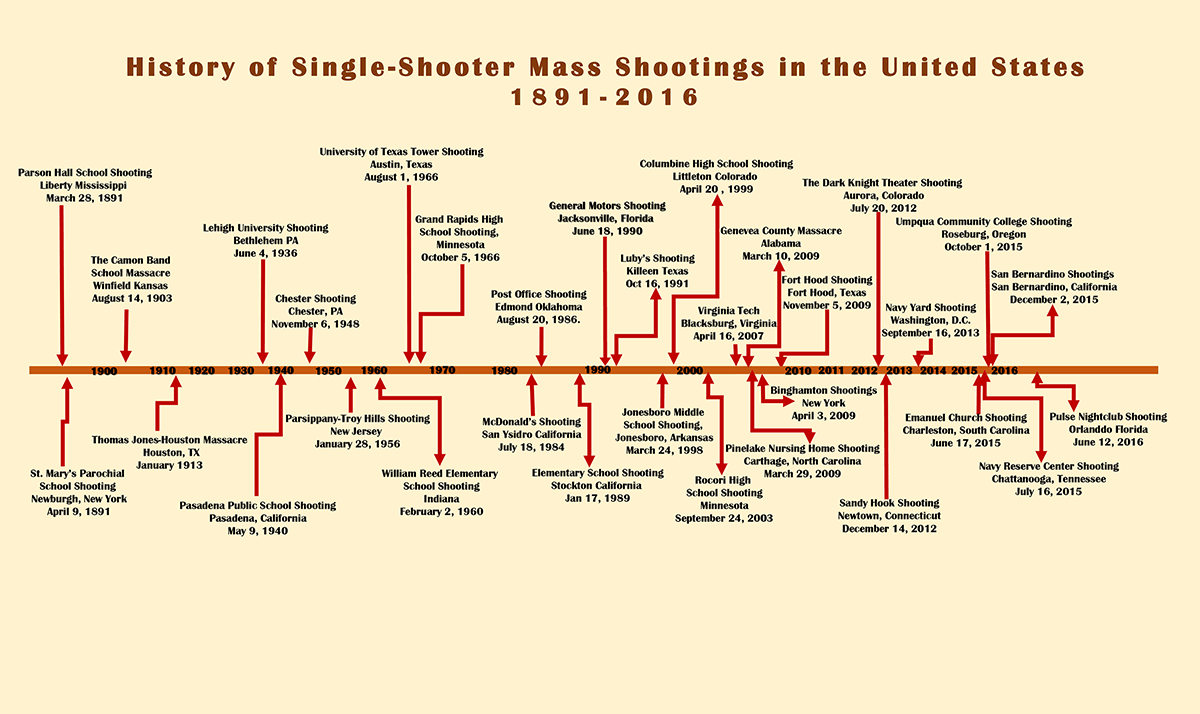

The notion portrayed by media outlets and the memory that materializes about the UT tower shooting in regards to it being the “first” violent school shooting, the “first” military-connected shooting, or even the “first” violent killing spree in the United States is a mythicized misconception. Historically the United States has witnessed many mass shootings, not originating from the UT tower shooting in 1966, but in fact predating that incident, and as early as 1891.The reasons that led to the August 1966 University of Texas sniper shootings and the perception that this incident was the first mass shootings in the country, not only demonstrates how our society acknowledges why violent crime happens, but also how the past is remembered through the perception of what is morally right and wrong, as well as because of our society’s tendency to so readily forget the past.

This brief history of violent crime in the United States, from 1891 to 1966 aims to shed light on how we understand violent crime, particularly why mass shootings happen through an examination of past mass shootings. It also aims to allow us to learn about how mass shooting incidents such as the tower shooting of 1966 are remembered, but also forgotten, and how this remembrance and forgetting have come to shape our perception of the continuity of mass shootings in the history of the United States, particularly before 1966, and the causes that deliver these. In order to comprehend the extent of Columbine, Charleston, Sandy Hook, and Virginia Tech and other mass shootings of today, however, we must examine those that happened in the past, and see how or if these historical occurrences have shaped how we understand the University of Texas’ tower shootings of August 1st, 1966.

The mass shootings and violent crime rates that we witness today, particularly those that happen on school property, or those related to military, or ex-military personnel are seldom a reflection of today’s generation, but reflect hard to explain violent crime dynamics that have existed for a long time in this country. Mass shootings have been occurring since even before the turn of the twentieth century. Disturbing and senseless shootings have occurred since 1891 in this country. On March 28, 1891 a man with a doubled barreled shotgun fired upon a crowd of students and faculty attending a school exhibition in Parson Hall School House in Liberty, Mississippi.1 The perpetrator wounded over fourteen people mostly children, with several being seriously wounded.2 This incident is perhaps one of the earliest reported school mass shootings in the country.

The incident that is regarded as the second mass shooting in this country happened a month after the Liberty, Mississippi shootings. On April 9, 1891 James Foster went inside St. Mary’s Parochial School in New York, and opened fire.3 The students he shot all survived, the trauma they experienced left a footprint that although undoubtedly hard to forget was in time actually forgotten. The mass shootings that occurred in 1891 appear to be so far detached, time-wise, that today they are little known. In 1966, when the tower shootings happened in Austin, the headlines of the day failed to recall any mass shooting that happened before the turn of the twentieth century, almost as if these had been erased in our society’s collective memory. The mass shootings that have followed the two 1891 incidents, those in the twentieth century, have become ever more constant, and even at times seem as being more acknowledged. Mass shootings in the twentieth century have been more included in the collective remembrance, even if they have been failed to be noted.

Mass shootings in the twentieth century have become ever so frequent that they have come to deeply shape our society and our current de-sensitized perceptions towards how we acknowledge, and remember, mass shootings in the country. The United States has witnessed a fair share of incidents since the early twentieth century, and although it is a painful task to examine the histories of these incidents, it is important that we do, for there may be many lessons to be learned from them. For instance mass shootings in the twentieth century can be traced back to 1903. On August 14 of that year Gilbert Twigg, a war veteran, deliberately fired into a crowd of people in Winfield Kansas immediately killing 9 and wounding 25 unsuspecting others.4 Thomas Jones a few years later also went on a murderous shooting spree on January 1913 in Houston, Texas as did Wesley Crow, a professor, who on June 4, 1936 shot and killed 5 in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania.5 The list continues to grow as we progress through the century. Other mass shootings happened particularly those within school settings such as the mass shootings that occurred on Pasadena Public School on May 9, 1940 when 30 year old Verlin Spencer opened fire on school property killing 4.6 November 6, 1948 was witness to Melvin Collins’s tragic shootings. Collins went inside the boarding house he had been living in, and decided to shoot people walking outside from inside his hiding spot inside the boarding house. Collins killed eight people and injured countless more. In a similar fashion an ex-military man, Howard Unruh, shot thirteen people and wounded at least five others in Camden, New Jersey on September 1949.7 William Bauer left seven dead including himself, in 1956 and Principal Leonard O. Redden on February 2, 1960, opened fire at a crowd of 30 students at William Reed Elementary.8 Mass shootings such as these listed here portray a history that is important to acknowledge and learn from.

The number of mass shootings in the past two decades have desensitized us or perhaps just helped suppress the memory of violent crimes, and how often these have actually happened. Mass shootings have render our society a sort of collective amnesia. This amnesia is hard to comprehend and examining the history of mass shootings creates more questions than lessons for us today. How should our society, our current generation, and our future ones as well, analyze these mass shooting incidents? How do we create connections from the past that can enable us to deal with the current wave of mass shootings that frequently happen today? Are the lessons from the past shootings that have occurred feasible to heed or are mass shootings an inevitable part of modernity that we must accept? Are the lessons that we can learn from past shootings able to better equip us on how to deal and how to heal from mass shootings that have wounded entire communities so deeply such as the UT tower shootings of August 1966? These seem to be quintessential questions, as relevant today, as they were at the turn of the century, in 1966, and even today.

What has become apparent through this examination of the history of mass shootings, however, is that the realities of what transpired on August 1st, 1966 at the University of Texas at Austin were unprecedented in both number of lives ended, number of individual lives affected, the extent of emotional damage perpetrated within both, UT’s and Austin’s communities, and the way in which public memory of the tragedy has since been overshadowed by factors that have been and still are hard to comprehend. The attitudes towards the 1966 shooting, both at UT and in the Austin community have seemingly created an abysmal amnesia towards the memory of this tragic episode, and towards how to acknowledge what happened and subsequently towards how to pave the road towards healing. The UT tower’s ninety-six minute shootings left 17 dead, including the shooter, thirty wounded, and many more maimed. These facts alone, for any community, in any era, and under whatever circumstance is a hard experience to process, let alone an experience sought to be examined. It is my hope that this brief history on mass shootings can open dialogue towards how the University of Texas at Austin can examine the past. How we, as both a community and individuals can take the lessons offered through our past history to help address the painful memory of the 1966 mass shootings, and hopefully in order understand how to begin to heal.